- Home

- Dyrk Ashton

Paternus Page 8

Paternus Read online

Page 8

“Sure.”

“I’ll be right back.”

Zeke tries not to grin as he watches Fi wrestle the big dog into the house. It looks like Mol has every intention of going in, he just doesn’t want to make it easy on her.

A few minutes later Fi retrieves her backpack. “Sorry about that.”

“No problem.”

“I even hooked his doggie door. Edgar’ll be home in a couple hours, anyway.”

They proceed up the sidewalk, neither of them knowing what to say first.

Zeke finally eases into it. “Beautiful day, huh?”

To which Fi abruptly announces, “The doctors don’t know why I have the seizures.” She waits for a response, but Zeke just looks on attentively. “There were a lot of tests when I was younger. It’s some form of epilepsy, but we don’t know where it came from.”

“That’s idiopathic.”

“What?”

“Idiopathic. It means ‘of unknown cause.’”

“Oh.” Fi does know that. “Yeah.” And of course Zeke does, the freakin’ walking encyclopedia. She thought he was saying something else. “I had the first one at my mom’s funeral.”

“Wow, sorry.” What else can he say to that?

“The doctors finally figured out the right dosage and combination of meds. I used to have to wear a medical bracelet and everything, but I haven’t had an episode since I was 12. We thought they were gone for good, that maybe it was just a phase or I was cured or something. Until last night.”

Zeke cringes with guilt. If the seizures are brought on by stress, he can only blame himself. “Fi, I—”

She cuts him off, “You won’t tell anybody, will you?”

“No, not if you don’t want me to—”

“Please?”

“I won’t. I promise.”

“Thanks. I mean, I know I should tell my uncle and inform the hospital, but they’d never let someone like that take care of the patients. And they’d be right to let me go, I know that, but it could’ve just been a one time thing, right? I’d get Edgar all worried and lose my job for nothing.”

“Fi, you don’t have to explain—”

“I doubled up on my medication, and if it happens again I’ll tell everybody, I promise.”

“Fi, I already said I wouldn’t say anything and I meant it, okay?”

“Okay.” Now she feels like a terrible-imposing-rambling ass. “Thank you.”

“Of course.”

Zeke is being so incredibly nice and understanding, so ingratiatingly Zeke-like, Fi hates to bring up the other issue, but he looks like he’s working up the courage to say something so she blurts it out anyway.

“I think maybe we should take some time off, not see each other for awhile.” She winces, hardly believing she actually said it out loud. She won’t look him in the eye, but she glimpses the shock on his face.

This is, again, not at all how Zeke expected this to go. Fi definitely has a way of keeping him on his toes. Maybe it’s part of the reason he’s so attracted to her. He can’t say he blames her. He wants to ask why, but he’s pretty sure he knows, and making her explain herself, to relive the rejection and embarrassment, would just be selfish and mean.

The silence gets really long, and really uncomfortable. Fi knows what’s coming, the inevitable blow up, or the pleading. Either way, she braces herself.

“Okay,” he finally says.

Well that was easy! she thinks. I guess I made the right decision!

“I want you to know, though, that I don’t feel the same way.”

Oh...

“I’m leaving for the conference tomorrow night, anyway, I guess—”

“Yeah. We’re both really busy and all.”

“But, can we talk when I get back?”

Now Fi’s very confused. Part of her wants to say “no” and be done with it. The other wants to take it all back and throw herself on him. What happens is she mumbles a noncommittal, “Sure.”

They come to a corner and Fi realizes where they are. “Um. I have to go that way,” she points, “and make a stop.”

“Mrs. Mirskaya’s?” Fi has told him about “Old Lady Muskrat” and her store. He’d like to meet her. She sounds like quite a character. Normally he would offer to go with Fi, but under the circumstances... “See you at the hospital?”

“Yeah.” She makes only brief eye contact. “See ya there.”

He forces a smile. “Okay.” She smiles sheepishly back. He has the walk signal, so he continues across the street.

Fi watches him stride away, his shoulders hunched. Her smile fades. What have I done now?

* * *

The bell hasn’t stopped tinkling above the door to Matryoshka, Russian Market and Café, before Fi is attacked.

“Fiona! Golubushka! (little dove!). Kak pozhivaesh?! (how are you living?!).”

Having grown up with Mrs. Mirskaya as a babysitter and then worked in her store for several years, Fi picked up quite a bit of Russian, but she can’t respond because her face is smashed between breasts that are each bigger than her head.

Mrs. Mirskaya releases her and kisses her three times, big wet smacks, alternating between cheeks. “Zdravstvu! (hello!),” she exclaims, “skol'ko let, skol'ko zim?! (How many years, how many winters?!).”

“It’s been two days,” Fi replies with a roll of her eyes. Mrs. Mirskaya always greets her this way. Ever since Fi no longer required a babysitter and then stopped working at the store, even though she comes in at least three times a week on her way to the hospital. It’s kind of a ritual between them.

“Too long, lapochka! (little paw!),” Mrs. Mirskaya reproaches in her wonderful old world accent, propping her fists on the broad waistband of her ankle length skirt. Old Lady Muskrat looks to be in her early sixties, a heavy-set woman with bristling black hair streaked in gray, more than a little dark hair on her creased upper lip, and prominent front teeth. She wears a vest she couldn’t button if she wanted to, because her enormous boobs shove out her blouse like intercontinental ballistic missiles preparing for launch.

She points at Fi with a knowing smile. “Today, I have just the thing for your Peter.” Fi wants to say she doesn’t have a peter, she’s a girl, but just grins to herself for thinking it and follows Mrs. Mirskaya, who’s already scurrying back to the counter.

Acoustic Russian romance music issues from tinny speakers, and the aroma of baking bread is heavy on the air. Not just any bread, but rich and black, made with molasses and dark rye. There’s also the cabbagy-oniony-beety smell of simmering borscht and a strong undertone of fish. Mrs. Mirskaya is always making borscht, but she’s either recently opened the chest refrigerator to scoop salty pickled herring from a barrel for one of her customers, or she’s been nibbling on vobla again and has fish-breath. Maybe both, but almost certainly the latter. Vobla are little fish from the Caspian Sea and the rivers that feed it, salted and dried. A lot of Russians eat them like potato chips, leaving only bones and skin, insisting they’re especially good with beer. Fi can’t even sniff one without retching. Mrs. Mirskaya munches on them all day long.

While Old Lady Muskrat busies herself behind the counter, Fi steps into a narrow aisle to wipe the warm dampness of the sloppy kisses from her cheeks. She’s very fond of the old Russian, but, Yuck!

Banks of fluorescent tubes cast uniform blue-green illumination over the tight space, with three rows of shelves piled to the tipping point. The walls are covered with hooks and racks bristling with goods. Not a square centimeter of space is wasted.

Fi eyes the shelves, shaking her head. When Mrs. Mirskaya restocks, she just fills up empty space with new stuff, taking very little care for organization. You might find the orange marmalade on one shelf and the lemon marmalade in a completely different aisle. Nobody complains. It’s part of the charm of the place. And if they can’t find what they want, they just ask. She angles her ample bulk and big pointed boobs down the tiny aisles and goes straight to it.

Th

e shelves were far more orderly when Fi worked here. She resists the urge to reorganize the scattered colors of natural hair dyes and instead wanders to the back of the store where café tables snuggle against walls covered with deep red wallpaper embossed in gold. Throughout the day, Mrs. Mirskaya offers simple Russian fare, tea, and vodka. Lots of vodka. This is where she taught Fi how to do a shot then sniff a piece of the black bread to clear her nose of the alcohol vapor and bite a pickle to kill the sting. Even in her early teens, more than a few times she left work with a warm buzz from a shot or two, or three. She was hoping to see a few regulars and say “hello,” but the place is empty.

Mrs. Mirskaya’s clear contralto voice floats song-like through the store. “Oh Fee-o-na! Vaht are you doo-eenk?” Fi squeezes back up an aisle to the counter.

“Hey,” she says, picking up a fuzzy Cheburashka doll from a basket on the counter and hugging its big round ears to her face.

“‘Ei’—zovut loshady!” replies Mrs. Mirskaya, who’s facing the other way, working on something that makes the sounds of crinkling paper and squeaking ribbon. The phrase means, “‘hey’ is for horses,” and Mrs. Mirskaya never misses a chance to say it, especially to Fi.

Alla Pugacheva sings a melodious love song on the sound system. Mrs. Mirskaya hums along. Fi suddenly feels mischievous, taken by the impulse to sing “Cheburashka’s Song,” from the Russian animated series. Cheburashka is kind of the Russian version of Mickey Mouse, and Fi knows every word of the song by heart. Her caretaker used to play episodes on old VHS tapes for her over and over again. Fi makes the doll do a manic little dance on the counter while she sings double-time, and loudly:

“Ya bil kogda-to strannoy

Igrushkoy bezimyannoy,

K kotoroy v magazine

Nikto ne podoydot.

Teper’ ya Cheburashka!

Mne kazhdaya dvornyazhka,

Pri vstreche srazu lapu podayot!”

In English, it means something like:

“I was a strange

And nameless toy,

Who at the shop

They would avoid.

But now I’m Cheburashka!

And to me every stray,

Offers up their paw, when we meet, right away!”

“Stop torture poor Cheburashka,” scolds Mrs. Mirskaya as she turns to the counter. In her hands are delicate violet flowers in a cone of green paper tied with white ribbon.

“Orchids!” Fi exclaims, dumping Cheburashka back in his basket and taking the flowers.

“Your Peter will like,” Mrs. Mirskaya states confidently, plucking a crispy strip of vobla out of a bowl on the counter and popping it in her mouth.

Fi breathes in the subtle bright scent of the flowers, which almost cuts the stink of fish. “Yes he will, they’re beautiful.”

Mrs. Mirskaya transfers half a dozen fresh Adriatic figs from a wood-strip carton to a small paper bag. “How is the starik? (old man?),” she queries.

“You mean Peter or Edgar?”

“Pssh! Chertik moy (you my lil' demon). Your uncle is not old. And he was just here yesterday for shopping.”

“Did you help him find his special mustard?” Fi asks with a sly smile. Mrs. Mirskaya eyes her suspiciously. Her husband died over twenty years ago, before she came to the U.S., and Fi has long suspected she has a crush on her uncle, so Fi drops hints or tries little digs to see if she can get a rise out of her. The old lady always dodges with talk of the worthlessness of men or just ignores her. Sometimes Fi teases her uncle about it, too. Edgar poo-poos the idea, saying “One woman in the house is quite enough, what on earth would I do with two?”

The last time she brought it up she asked him, “You know what they say about a woman like that?”

“I do not, and I don’t think—”

“Shade in the summer and warmth in the winter.”

Edgar blushed, said “Oh my...” and scuttled back into the kitchen.

“Peter’s doing fine, I guess,” Fi responds, unshouldering her backpack. “Not much change, for better or worse.”

“Not for worse is good, no?”

“Not for worse is good, yes,” Fi answers. “Thank you for asking.” She stuffs the figs into the bottom of her backpack and carefully slides the flowers in along the side. Her demeanor turns serious. “But today, you’re letting me pay,” she asserts, pulling money from a side pocket.

“Keep your dirty American money,” says Mrs. Mirskaya, crossing her arms defiantly. “Is no good at Matryoshka.”

“Come on,” Fi pleads, offering the cash. “You can’t—”

“I do not see what I am seeing!” she interrupts.

“But those are orchids! How much—”

“I do not hear what I am hearing!” she shouts, or sings, more like, steamrolling Fi’s words.

“You can’t keep giving...!” but the sturdy Russian is already turning the music up and singing along with Alla Pugacheva, her voice vibrant and obstreperous. “Mrs. Mirskaya!” Fi cries, “you’ve got to let me pay sometimes!” The shopkeeper pulls her Russian bayan accordion from beneath the counter and plays it as well as sings, completely drowning Fi out.

Fi shoves the cash in her pocket, exasperated. This is how it goes every time since Fi stopped working here—they annoy each other, on purpose, then Fi tries to give her money and Old Lady Muskrat refuses—though usually it isn’t quite so dramatic. Fi doesn’t dare buy the flowers and figs anywhere else, though. Mrs. Mirskaya would take it as a terrible insult, and Fi realizes deep down that doing this for her makes the old woman happy.

Fi slings her backpack on, stomps to the door, but when she turns back she can’t help but smile at the sight of Mrs. Mirskaya singing, playing and swaying away behind the counter. Fi waves. “Spasibo! (Thank you)! See you in a few days!”

The woman who played nurse-maid, mentor and practically mother to Fi over the not-so-many years nods and does a theatrical little turn.

Halfway up the block, Fi can still hear her sonorous voice and the piping chords of the bayan.

* * *

The sun continues to hold its own, pressing a gap of flawless blue sky between cottony clouds. Fi steps along the sidewalk, enjoying its warmth and light. The lovely weather does little to smarten the stark city streets in this area of town, with their cracked concrete, heaving asphalt, abandoned brick buildings and chain link fences embedded with soiled white litter. The passing of an occasional car, a few ratty-looking sparrows flitting by, and stalks of sickly weeds are the only signs of life on this quiet Sunday morning.

A few blocks ahead is St. Augustine’s, the hospital where Fi works. The six-story building of caramel-colored brick was once a YMCA, shuttered in the 1980s. A few years ago it was renovated by a corporation that operates several hospitals in the area with a considerable grant from an enigmatic philanthropic group called The October Foundation. The grant, which amounted to hundreds of millions of dollars, came with the stipulation that it be used to create a long term care facility for elderly patients who are both indigent and suffering mental illness. Peter, the old man Fi spends most of her time with, meets both criteria.

She began working at the hospital three months ago, thanks to an internship program between St. Augustine’s and the university’s medical campus. Peter was discovered on the front steps her very first day, his only identification a torn slip of paper that read Peter, pinned to his shabby baby-blue bathrobe. Fi had gone outside to help bring him in, and though he was practically catatonic, lying there in his old-fashioned night-cap and matted pink slippers, for one brief moment he looked right at her. A smile crept across his gaunt wrinkled face and he inexplicably said, “There you are!” He hasn’t spoken anything quite so coherent since.

The doctors chalked Peter’s condition up to “severely impaired global cognitive faculty.” Dementia, in other words. He was relegated to the north hall of the fifth floor where untreatable patients are sent to wait out the end of their days.

Fi hadn’t

given up on him, though. Zeke has been a great help too, and Big Billy, an orderly at the hospital. It was Zeke who found out that Peter had an affinity for the song “Greensleeves,” and Billy discovered his infatuation with the stars. But it’s Fi whom Peter relates to the most, if you could call it that, and she who brings him flowers and figs.

In her first week, she was making rounds with one of the doctors and they checked on Peter in his room. Amidst his usual incoherent mumblings she thought she heard him say “flowers and figs,” over and over. She figured, what the hell, I’ll give it a shot, and brought him daisies and the sweet little fruit from Mrs. Mirskaya’s market the next time she came to work. The response was extraordinary. Even the doctors took notice. Peter actually clapped his withered hands—quite an accomplishment for him—and held the daisies under his nose all day. Which is kind of funny, since daisies smell like ass. Since then, Fi’s been assigned to Peter every time she works. Every once in awhile he smiles when she arrives. Those are the best days.

Most of the time she just walks him through his various therapy sessions, makes sure he eats something and sits with him while he watches TV (though what’s happening on the screen doesn’t seem to register). She reads to him too. Anything will do, even medical journals, which she borrows from the doctor’s lounge. Sometimes she’ll sit next to him and just flip through the pages while he stares at them. The faster she turns them the more he seems to like it. Something about the repetitious movement appeals to him, she guesses, because he certainly can’t be getting anything else out of it. The patients have no computer access, but she occasionally sneaks him into an empty office and clicks through screens for him, surfing the web. If he perks up, she’ll follow certain threads. Some of it’s important stuff, news, world events, science, but mostly they watch music videos and stupid human tricks on YouTube. A lot of the time, when they’re alone, she just talks to him, telling him random stuff about her day, school, even boys, and Uncle Edgar. She senses he might be most interested then, as much as he is capable.

Fi waits for a TARTA bus to pass and crosses the street. Her thoughts return to Zeke, like restless fingers to a fresh bruise. She’s been attracted to him since she first laid eyes on him, playing his guitar in the hospital rec room. She’d catch him watching her sometimes, too, but for a long time she was unable to form words when he was near. She’s convinced all the women want him. Of course they do. He’s hot!

Paternus

Paternus Paternus: Rise of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 1)

Paternus: Rise of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 1) Paternus: Deluge, A Short Story

Paternus: Deluge, A Short Story Paternus_Rise of Gods

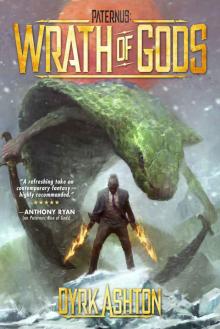

Paternus_Rise of Gods Paternus: Wrath of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 2)

Paternus: Wrath of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 2)