- Home

- Dyrk Ashton

Paternus Page 5

Paternus Read online

Page 5

Bödvar knows about the disappearance of The Madman, of course, and that no one had been able to find him after his imprisonment. Some of the rest of what Baphomet said makes sense now, too. Bödvar spent most of the time waiting for his mission watching “television” and “surfing the net,” absorbing what he felt was important (and wishing he could forget the rest). He can even hold his own with the modern English now. Firstborn learn fast. Much has changed in this world, he has to admit, over an astonishingly short amount of time. One thing hasn’t, he’s glad to see. There are still wars.

The rucksack hums again, lilting and reedy, oddly amplified by the vessel in which Bödvar’s “partner” on this mission is contained. He can’t place the tune, but whatever it is, it’s extremely annoying.

“Hush!” he shouts. It doesn’t stop. He raises his hand to rap the top of the pack again but decides against it. He’ll have to let it out soon. He’d rather it not be too angry with him.

He turns his attention to the bright glowing screen of a device that looks tiny in his enormous paw. Baphomet gave him this little box of “electronics,” which he called a “GPS,” and insisted that Bödvar use it to find the cave. It’s pretty simple, really. Green dot pinpoints where he’s located on the digital map, red dot marks where he wants to go. The two dots are right on top of each other.

He’s here.

He eyes two large ash trees that stand against the face of a bare limestone cliff, then checks his surroundings. Fairly secluded. More trees provide cover, and he can’t see the path a hundred yards back down the hill. That won’t help when he starts pounding on rock, though. The sound may be heard for a mile. Once he begins, he’ll need to keep his hearing and sense of smell keen to approaching parvuli.

But right now there’s another problem. The night is retreating, pursued by the faintest hint of daylight to the east. The sun will soon be revealed in all its glory by the unstoppable spin of the earth. Birds are already chirping.

Fucking birds!

Bödvar growls and chucks his hammer to the dirt. Here he stands, right where he needs to be, and he’s forced to find someplace to hide and while away the day, then return when night comes again to complete his task. That was a most adamant command of Baphomet. “Do not open the cave in the light of day, under any circumstances.” All part of the Master’s “master” plan, Bödvar figures. Or maybe it’s for the benefit of his partner in the rucksack. From what he’s heard, it’s not a fan of daylight.

Well, there’s nothing for it, he’s going to do what he’s told. He groans, picks up his hammer and stomps off to find someplace to wait out the sun. The rucksack sloshes and hums as he shoves through the brush.

“Hush!”

CHAPTER FIVE

Order of the Bull

How does she move her tongue so fast?, ponders the little round fellow in the long fur coat. No matter how many times he hears the trilling wail of zaghruta singing, Tanuki is always amazed. The scantily clad performer of the oryantal dansi approaches the fruit stand where Tanuki clutches half a dozen small crates of dates, undulating her body in seemingly impossible ways beneath her bedleh costume of shining gold and turquoise. An ensemble of musicians huddle against the stone cliff in an empty space between vendors, fervently playing reed flute, drum, fiddle and lute. The shapely mtoto female circles Tanuki, whose ample cheeks could be seen to blush if he didn’t have a dense, close-cropped beard of the same peppered tan as his fur coat and the Russian ushanka-style hat he wears with the ear flaps up.

The dancer’s braceleted arms move serpentine above her shoulders. She lightly brushes the fur of his hat and his beard with her fingers then backs away, her pelvis gyrating so quickly the beaded rainbow belt above her scanty skirt is a blur. She smiles at him, lets loose another shrill zaghruta wail. Between her staccato hip movements, the gem in her navel and her vibrating tongue, Tanuki is captivated.

“Master Tanuki?”

Tanuki snaps out of his musing as a distinguished looking, elderly mtoto woman approaches. “May I take that for you?” she asks in modern Turkish. She is the High Abbottess of their sect, the Order of The Bull, in charge of day-to-day management of the monastery, as well as an Apis High Priestess.

“Yes. Thank you,” Tanuki replies in the same language. He hands her the wooden boxes of dates, nodding with regard.

The Abbottess passes them to a young man, a Cellarer Novice, who looks up at a wagon mounded high with goods, calculating how to make them fit most efficiently for the long trek home.

Tanuki’s cohort of monks consists of six men and six women, all dressed alike in tagiyah prayer caps, white shirts with billowed sleeves beneath cepkens (a type of Turkish vest), drab baggy pants, and a sash. Each carries a wooden staff with a woven strap attached.

Tanuki and this group from the monastery camped nearby last evening, then rose well before daybreak and arrived at the bazaar early this morning when many of the merchants were still setting up their booths along the rock walls on both sides of the narrow canyon. They’ve been haggling and packing since. Space is running short. The two wagons they brought with them, each pulled by four small but sturdy Anadolu horses, and the six mules and another dozen individual Anadolu are all laden with wares from the day’s procurement. Each man and woman of the group wears a canvas backpack, all loaded with goods as well. This is the last autumn bazaar in this remote area of Anatolia, in the north-east of Turkey, and they are stocking up for the long winter in the Kaçkar Mountains where their monastery is located.

They have many hours of travel ahead of them. Tanuki squints at the sun. Just after 7 a.m., time to go if we’re going to make it back by nightfall. He digs into his purse and drops a generous helping of Turkish liras into the porcelain bowl on the ground near the musicians, at which they marvel.

He smiles at the Abbottess, who nods their readiness. Two young monks hurry to Tanuki, toting a hefty backpack between them. They strain to lift its weight to his shoulders, but he slips his arms through the straps, receiving it with ease. He bows lightly to the young men, placing his palms together in the Buddhist añjali-kamma gesture. The caravan makes its way through the crowd.

This is a rural market, very unlike the lavish Grand Bazaar of Istanbul. There are no soccer shirts, cowboy boots, or bootleg movies here. They pass tables of oils, spices, nuts, dried beans and durum wheat. Neat piles of fruit and carts mounded with vegetables. They have purchased plenty of all of these but nothing from the many stands of meat and fish, not even the Turkish staples of sardines and anchovies. All of them in the Order are vegetarian by choice—though Tanuki has snuck some etli yaprak sarma today, vine leaves stuffed with flavored meat and rice, while the rest were otherwise engaged.

They pass vendors dishing out spicy sucuk sausage and kebabs. To drink, there’s tea, Turkish coffee, thick and sweet, and cacik, a thin yoghurt beverage with minced cucumber. Others ply a staggering variety of cheeses, soups, breads and sweet pastries. Tanuki has sampled much of it, far more than he needs, but the savory aromas still taunt him. He expresses a visible sigh of relief when they are past the food stands to the dry goods. Booth after booth of traditional clothing of bright and colorful design, vibrant vases, finger bowls and plates of every imaginable hue, some decorated with intricate Iznik floral designs, others with luxuriant painted grapevines. Tanuki browses past tiers of embroidered kapalicarsi, handmade Turkish shoes. He always wanted a pair, though they’d never fit his fat furry feet. He considered commissioning a custom made pair but was convinced by his Brothers his toe claws would probably shred them in short order.

Then there are the sellers of the world famous Turkish carpets and rugs. Tanuki brushes his hands lightly across them, feeling the differences in texture and weave. The cheerful merchant doesn’t mind the fingering of his merchandise. Tanuki acquired the finest and most expensive rug at the bazaar from him earlier this morning, a gift for Big Brother Arges.

They hear the music before they reach the gathering crowd. Besides

offering the prospect to buy and sell goods, this bazaar also provides the locals with an opportunity to celebrate the fall harvest. Tanuki grins. And the Turks never shirk their celebrational duties.

In an open circle where the canyon widens, six men in black caps with vests over white shirts and pants tucked into high black boots are lined up, hands on shoulders, moving deliberately and dramatically to the accompaniment of traditional folk music. The crowd around the circle claps in time as the dancers swing their legs, sway, and stomp in unison.

Tanuki applauds with delight. He’d dearly love to join the dance or snatch up one of the musician’s shepherd’s pipes, fifes or baglamas and play along with them. He could easily catch up with the monks if he were to send them on ahead but it wouldn’t be good etiquette. He nods to the Abbottess and they continue on their way.

Abruptly, it seems, they’re passing out of the east mouth of the canyon into the clear autumn air, the stony rolling countryside laid out before them, the sounds and smells of the bazaar fading away behind.

Tanuki drops back to confirm with the Cellarer Novice that all the dates have been packed securely. He has taken pains to purchase plenty of dates today, his Brothers back home will be happy to see, and would be mightily sore at him if he hadn’t. Asterion The Bull and Arges The Rhinoceros do love their dates.

* * *

The cavalcade of monks travel east over the undulating, rocky terrain, the mountains to their left and the Çoruh River valley to their right, the only sounds the muffled clopping of the animal’s hooves and the soft conversation of the monks. Humps of spiny thorn cushion and milk-vetch spread sporadically as far as the eye can see, the multiplicity of tints of summer having given way to the gray and brown of coming winter, soon to be covered in white. The formerly colorful Asteraceae now reduced to swaying thistles, and all that’s left of the glorious flowering mulleins are bare stalks rising from rosettes of velvety leaves lying flat on the ground.

Eventually they angle north toward the mountains. Not far to the south and east are the trickling waters that form the beginnings of both the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. Some call the Euphrates-Tigris Basin the “cradle of civilization,” others claim the Nile River Valley deserves that designation, still others the Yellow River Valley of China or Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. They are all deserving, and not, Tanuki muses. These areas were all home to early “advances” in mtoto culture, but there are plenty of other places in this world where civilizations have waxed and waned. Not all of them were mtoto, or particularly “civilized.”

In ages past lions and tigers roamed these steppes, but they’re long gone. Tanuki still hopes to catch a glimpse of a rare Anatolia Leopard, though. He fondly recalls venturing out with Arges in bygone days, surreptitiously destroying pitfall traps the Romans set to capture leopards for gladiatorial spectacles. On one occasion they spied a half dozen Roman centurions approaching so Arges hid in one of the pits. When the centurions peered in to see what they’d caught, he sprang out with a mighty roar. Three of them shit themselves, one fainted. Tanuki has never seen watoto run so fast.

Chuckling to himself, Tanuki sees he’s outpaced the group. There’s a pond near the path, so he calls back to ask if they’d like to rest. The monks are extremely fit, but they don’t protest and are happy to tend to the horses and mules.

Tanuki removes his backpack and wades into the clear shallows of the pond to enjoy the refreshing coolness on his bare feet. He looks down into the mirror surface of the water. To his own eyes, the mtoto cloak he wears outside the monastery is gone.

Thanks to the unique physicality of their father, all Firstborn have the ability to alter their form to some extent. A combination of an actual reorganization of matter and a psychological projection, in varying degrees. Tanuki usually doesn’t bother with a physical change because he isn’t enormous, very oddly shaped, or four-legged, and he doesn’t have pesky horns or antlers to get in the way. For Tanuki, simply impressing upon the acuity of watoto is enough.

Mtoto perception is very practical and became more so as they evolved, governed by their sensory-motor schema of stimulus-response, action-reaction and habitual recognition—essentially, the need to immediately make sense of what their senses bring to them and determine its use value or whether it is friend or foe. This also, however, limits them. They have a very hard time seeing what they don’t understand or have never seen before.

Since the watoto are naturally inclined not to perceive Firstborn as they truly are, with very little effort Tanuki can “project” a familiar appearance, much like a human can project an air of confidence, strength, or sexuality. Without saying a word, even watoto can appear to be confident, strong, or sexual to those around them, even if they are timid, weak, and terrible in bed. Thus, in the presence of watoto, Tanuki can simply consider himself a jolly bearded fellow in fur coat and hat, and voilà, that’s how the watoto perceive him. It doesn’t work on animals, or some small children, but the grown-ups don’t pay much attention to them anyway.

Since Firstborn are fully aware of their own existence, they can usually see through the cloak of others with ease. Whether they wear real clothing, the illusion of clothing, or none at all, it matters not. Some are better at cloaking than others and can take all manner of forms, particularly the elders. Most, like Tanuki, always retain characteristics of their Trueface, just morphed to human understanding. Like all of them, however, Tanuki can easily appear as the species of his mother, as a lump of earth or stone if he lies still, even a shadow in dim light.

It is kind of sad that the watoto are so easily duped, but this simplistic perception of theirs is also the primary reason they’ve survived as a species. There are advantages to going though life with blinders on. If at any time throughout their existence they had full comprehension of how truly vulnerable they were, any real inkling of the odds against their survival, they may have just lain down to die. Thanks to their unlikely combination of qualities, however, being at once brilliant and ignorant, adaptable yet naïve, and most of all tenacious, they’ve now reached the highest rung of the evolutionary ladder. Well, almost.

Tanuki contemplates his reflection. He’s little more than 5’ 8” tall but more or less humanoid in shape. A bit on the chunky side, though he likes to tell Arges that it’s because of the fur. His arms and legs are as hairy as the rest of him, with short black claws on his stubby little fingers and toes. He has a wet black dog’s nose, deep brown eyes and sharp little canine teeth top and bottom, with fuzzy peaked ears high on his head. There are dark circles around his eyes, but they aren’t from fatigue. Tanuki may be young for a Firstborn, but all have endurance and constitutions far beyond that of any mtoto. He could carry his pack at the pace they’ve been keeping today for weeks on end, without food, drink or repose. He wouldn’t like it, but he could do it. No, he isn’t tired. He has circles around his eyes because he’s Tanuki. The Tanuki, in fact. The only one left. It’s just the color of the hair there. He gets it from his mother, a natural Tanuki, Nyctereutes procyonoides viverrinus, a canine species native to Japan that survives to this day. They’re also called “raccoon dogs” because of their surprising resemblance to the nimble-handed creatures, right down to their short pointy snouts, bushy tails, and black bandit masks.

Tanuki has all those traits, including the bushy tail, though he can’t see it in his reflection because it’s behind his butt where tails are supposed to be. He can see his big fuzzy balls, though. It’s difficult not to, considering the angle of the water below and the fact that they are pretty big. But they’re covered with short dense hair, the same color as the rest of his fur, so he doesn’t consider them obscene or even all that obvious.

He’s stirred from contemplation of his fuzzy nutsack by a high whistle, the sound of the Abbottess signaling the monks to prepare to move on. Tanuki ascends from the pond and stoops to his backpack. In a blink he’s cast in shadow and out of the corner of his eye he sees a dark patch flit across the sun’s reflection

on the water. He jerks his head up and scans the sky, but there is nothing there. He looks back at the monks, who are busying themselves with a final tightening of straps on the wagons. There’s no indication they’ve noticed anything out of the ordinary.

Just a wisp of cloud, or maybe a bird, he rationalizes. But there are no clouds, and it would’ve had to be a damn big bird. Must have been a jet. A very fast, high-flying jet.

Gullible as ever, he scolds himself. Still, he has a hard time shaking the inexplicable chill that’s come over him.

CHAPTER SIX

Flowers & Figs 2

Fiona Megan Patterson wakes. I’m supposed to remember something, is her first sleepy thought. Aren’t I? A dream, maybe? She knows she dreams, but she doesn’t remember many. That’s very common. She’s read about it.

Fi stretches under the covers, groans and looks out her bedroom window. The bright morning sunlight has turned the paisley design of her lace curtains into a soft white frieze.

Surprise of surprises, she’s woken up horny. Imagine that! It’s a curse, she swears, one she’s had to bear every day since puberty. The memory of last night floods back. Not only did she not finally have sex, she was totally humiliated as well. And had a seizure! Right in front of Zeke! She moans, mortified, pressing her forearm over her eyes. It’s not just the humiliation or the “relationship” problems, either. She hasn’t had an episode in ages. What if they’re back, for good? She decides to keep it to herself for now. Meanwhile, she’ll just have to live with the nagging fear that it could happen again, any place, any time. She remembers that feeling. It sucks.

Paternus

Paternus Paternus: Rise of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 1)

Paternus: Rise of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 1) Paternus: Deluge, A Short Story

Paternus: Deluge, A Short Story Paternus_Rise of Gods

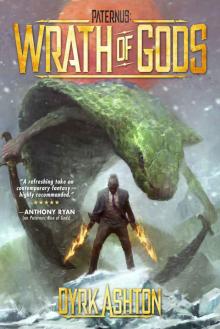

Paternus_Rise of Gods Paternus: Wrath of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 2)

Paternus: Wrath of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 2)