- Home

- Dyrk Ashton

Paternus: Rise of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 1) Page 4

Paternus: Rise of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 1) Read online

Page 4

Most of the Firstborn are now dead and forgotten. Even the knowledge of those still living endures only in myths and hushed fables told to frighten troublesome parvulus children. For the most part, today’s humans not only don’t realize Firstborn exist, they don’t believe they ever have. Except for a precious few, the most primitive and faithful among them, they’ve completely forsaken the gods and monsters of their forefathers. Ao grins as much as the structure of his gharial mouth will allow. That’s all about to change.

He snaps his jaws again, the interlocking teeth clearly visible even with his mouth closed, and takes a deep rumbling breath, concentrating on the task at hand. Clear nictitating membranes open downward over vertical black pupils. He eyes the altar then peers at the openings of two crevices, one in either corner at the back of the chamber.

“Looks like the right kind of hole for a Firstborn.” He speaks in pre-Sino-Tibetan, from before the last Ice. His voice is deep and grating, the sound of shoveling gravel. The lips at the bulbous end of his snout move like a human’s might, but spiky teeth protrude every which way, forcing him to enunciate deliberately.

“I’ve stayed in a few like this myself,” Baphomet replies. He’s smaller in stature than Ao Guang, less than six feet tall, but his horns rise as high as the top of Ao’s massive head. They call him The Goat, though his mother was more like a mountain Ibex. Still, his knees bend backward like his mother’s did, and the pink irises of his eyes are cut across by horizontal pupils. Unlike his bovid mother, however, he has humanlike teeth with sharp incisors--gifts from Father, like his roughly humanoid physique--and a taste for flesh.

Baphomet is fully aware that Ao Guang resents him, considers him a shameless seeker of status and attention, but he couldn’t care less. Besides, it’s true. He’s always garnered worship from Firstborn and parvuli alike. He likes the company. He’s had to operate in the shadows since the Second Holocaust, careful to avoid the prying eyes of Father and his loyal Deva, but he’s been manipulating humankind through dark cults and secret societies for millennia. At one time he had hundreds of thousands of followers all over the world. There are still quite a few. Some hold positions in the highest echelons of government and industry.

Recently, he and the Master combined their significant resources to seek out and assemble the remaining Asura, the Firstborn who opposed Father in the First and Second Holocausts, as well as locate their enemies, the Deva, Father’s Firstborn warriors.

It hasn’t been an easy task. The Asura lost both great wars, and those who survived have been hiding or sleeping for much of the last two myria. Until only a few years ago the mighty Ao Guang, once worshipped as the Dragon King of the Eastern Sea by clans who later became the Chinese, was lolling in the mangrove eco-regions of West Africa where the natives whisper warnings of a terrible beast they call Ninki Nanka. Dimmi had been less reticent. Maintaining his human cloak, he’d been hiring himself out as a mercenary to whomever would pay the most in diamonds, gold and flesh. He was prowling Sub-Saharan Africa, taking advantage of the strife there to fuel his fiendish proclivities for torture and rape, when the Master and Baphomet approached him.

Now after centuries of preparation, they’ve recruited enough of the surviving Asura and learned the whereabouts of a sufficient number of Deva to proceed with the master’s plan.

At the last minute, their networks submitted a report of a mysterious swamp beast in one of the most inaccessible regions of South America. The Master’s scheme was already in motion, but he doesn’t like loose ends. Three days ago Baphomet, Ao Guang and Dimmi were air-dropped by helicopter into the muddy Brazilian Amazon River, just over the border from Peru. They are tasked with finding out if the rumors of the creature are true, and if so, if it is Firstborn. They are to recruit it to the Master’s cause if possible. If not, they’ll just have to kill it.

It rained the first two days they slogged through sucking mire and clinging jungle in search of the unidentified swamp beast. Eventually they followed a tiny tributary because Dimmi smelled smoke, and came across a tribe of native parvuli, naked and brown, who’d been entirely undaunted by the sight of the strange adventurers, even when they revealed themselves in Trueface.

The natives proved remarkably stolid. One by one they were questioned while the others forced to watch. Ao Guang hung them upside down over a fire pit, reveling in their screams, the odor of burning hair and roasting flesh. Other than the wails of agony of the tortured, none of them uttered a word. Only the last surviving among them, a female child, finally spoke of a powerful bruja, a witch who appeared out of the jungle to heal them when they were sick. But only after Dimmi painstakingly chewed off her soft grubby hands and gnawed one of her arms up to the elbow did she confess her people made offerings near a hidden lake located to the north. Dimmi had taken this as good news, particularly liking the idea their quarry was female. The Goat himself was encouraged, though it gave him pause. There have never been many female Firstborn, and they are strong.

The moans of the dying girl followed them into the undergrowth, her last words prophesying agonizing deaths for what they had done to her people. Ao Guang has spoken little since. In silence he dove through the reflection of the full moon into the black water of the lake and discovered the flooded tunnel that brought them here.

Baphomet studies the cave. This place is old, he thinks, the cavern cleft from fissures in dark purple volcanic glass, born in a rhyolitic eruption when this earth was young. The temple within it is not so very old, however, he considers as he eyes the torches and altar. He has been in this area of the world before, most recently along the coast of what is now Peru, “vacationing” with the Master amongst the Moche culture, sharing with them the joys of hematophagy. The glyphs carved in the edges of the altar are from a society older than the Moche, pre-Olmec even, but are still of parvulus origin and hold no power over him. They represent utterances of protection and healing. Pathetic. They’ll protect no one today. There are three of them, and they have The Gharial. Ao Guang may not be a True Ancient, but he is one of the oldest surviving Firstborn, reared in the age immediately following the Cataclysm on what is now the land mass of East Asia--though when he was young, tectonic drift had not yet brought that part of the world to precisely where it lies today.

Dimmi sniffs the air.

“What is it?” Baphomet asks.

Dimmi moves cautiously to peer into the darkness of the crevice to the right, but something else catches his attention. He yips and jabs a clawed finger at the area behind the altar.

Dimmi’s Truename, the name bestowed upon him by Father at birth, is Idimmu Mulla, words the Sumerians later incorporated into their language to mean “demon” and “devil.” His mother had been one of what parvulus paleontologists have dubbed Pachycrocuta brevirostris, an extinct species of hyaena. Heavyset creatures that weighed over 400 pounds. He has many of his mother’s physical traits, but the shape of his head is more humanoid, more so than either Baphomet’s or Ao Guang’s, which makes him even more terrifying to parvuli for some reason. His sloped shoulders are positioned low on his body, supporting a long thick neck, and his hands almost touch the ground. He’s as tall as Baphomet (sans the horns), and rippling muscle bulges beneath his furry hide. He’s far younger than Ao Guang and less than half the age of Baphomet, but Baphomet has seen him defeat older Firstborn and would not relish coming to blows with him--though he’d never let Dimmi know that.

Baphomet runs his hand along the slab atop the altar as he edges around it. Each of his five fingers ends in its own small cloven hoof, shiny and black. On the floor behind the altar he sees a familiar sight, a five pointed star, rendered with a smudge stick of burnt ash. He isn’t old enough to have invented it, but he knows the sign of the pentagram all too well. He prefers his pentagrams inverted, however, and this one is not. He was the first to turn it on its head, though it was against his wishes one of his abecedarians, Stanislas de Guaita, incorporated the face and horns of The Goat within the s

ymbol when Baphomet revived one of his ancient cults as The Cabalistic Order of the Rosicrucian in France.

The pentagram isn’t all there is to the figure on the floor. It’s drawn within an octogram, an even older symbol, and both are placed on a tightly wound spiral of lighter ash, laid down before the octogram and pentagram were etched over it.

Baphomet raises a hand to his chin and strokes his tuft of beard in contemplation. The other hand he holds loosely in front of him, rhythmically clicking the little hooves together. Click, click, click.

That’s not a good sign, Dimmi worries to himself, wringing his hands. He only does that when he’s anxious about something, or confused. And Baphomet is very rarely anxious or confused.

Ao Guang concentrates on the two crevices that lead from the chamber, trying to ignore Baphomet’s annoying clicks and Dimmi’s incessant fidgeting.

Baphomet crouches and runs the twin hooves of a pinky finger through the charcoal lines at the edge of the octogram. On the far side of the symbol is a ring of river rock around a burnt-out fire, near it a heavy copper kettle of no special construction or origin and a number of chalices of various composition, including one of ruby glass. Around the upper curve of the symbol various articles are arranged. A tortoise shell, a mortar and pestle of basalt, a weaved cingulum coiled up, a pile of twigs from an almond sapling. Leaning against the wall is a besom (a witch’s broom), and a stang--it’s not unusual such a staff would have two prongs at the top made of antler, such as this one has, but these come from an animal that’s been extinct for at least six epochs.

Baphomet turns his attention to crude palm-leaf shelves erected along the back of the altar’s base. Each is lined with blown glass bottles of herbs and attars, many of which he recognizes by sight or smell. Balm of Gilead, Hyssop, Linden Flower, Tamarisk, Yerba, and Yew. There are many others he can identify, and more that he cannot.

Hanging on leather cords from spurs of rock at the back edge of the slab are three talisman pendants. Baphomet fingers the first, made of precious green Jadeite, then the second, black Serendibite, and the last... Baphomet lifts it gingerly by its cord, careful not to touch the pendant itself, which is metallic but bright red, the color of fresh blood. The first two are made of some of the scarcest stones in all the worlds. The only rarer are found infrequently in the fragments of meteorites, the only source he can imagine the material of this third pendant coming from.

He replaces it and rises, crossing his arms. These are all standard wares of parvulus witches, wiccans, warlocks, shaman, sorcerers and wizards alike, all who claim to have special powers. Charlatans, for the most part. Nevertheless, they are from all over the world, and some are very, very old. The name of The Madman comes to mind, but Baphomet knows exactly where he is, buried in England, and another team of Asura are on their way to him this very day. Baphomet has also noticed that some customary objects used by human magi are missing. No wing bone of an eagle, foreleg of wild boar, human foot or tail of cow, and not one eye of newt. What perplexes him more, however, is a single rune inscribed into each of the three pendants, all of them different, and he does not recognize the symbols. They look something like the Enochian glyphs conjured up by two of his lesser pupils, the 16th century whelps Billy Dee and Edward Kelley, but these are different. Simpler, in a way. Primal. Beautiful, really.

Baphomet strokes his goat-beard pensively, commences once more to clicking the finger-hooves of his other hand.

Dimmi resists the urge to flee. Baphomet’s behavior is very peculiar and it has him rattled. I am not a coward!, he tells himself. I just have a strong inclination for survival. A yip and chitter rise in his throat, but he swallows them down. He knows Baphomet trusts him, or at least trusts him to fear their master enough to do his bidding. I cannot fail! There’s also the Master’s psychotic sidekick to consider. Dimmi shudders at the thought of Max, resumes bouncing softly where he stands and scratches the backs of his hands nervously. Next to the predilections of Max, Truename Maskim Xul, Dimmi’s own diabolic tendencies pale.

Dimmi begins to laugh, a harsh giggle-shriek/cackle-bark. He does it when he’s nervous, a habit he acquired from his mother he’s never been able to break. He sees Ao Guang glaring at him with his slitty green eyes. Stop it! Dimmi rebukes himself. You’re better than this! But he can’t help it, and he’s getting louder.

Baphomet is about to reprimand him, as well as suggest they do not split up to search the cavern, when they hear a faint scraping from deep within the crevice nearest Dimmi.

Dimmi leaps back to the top of the steps at the edge of the pool and crouches on all fours. Baphomet backs around the altar to stand next to him. Ao Guang looms over them both. All three peer intently into the darkness.

The scraping continues, and deep in the fissure they see light. A dim, purplish glow. Slowly, the light moves closer, spreading from the depths, and they realize it’s the obsidian walls themselves that emit the soft luminescence.

Baphomet squints and thinks he can make out a hand--thin, dark, clawed--sliding along the wall of the tunnel, at the leading edge of the advancing radiance. Then they hear something else. A low murmur interspersed with clicks and grunts.

“What is it?” Ao whispers above Baphomet’s ear.

Baphomet does not take his eyes off the light.

All Firstborn have an innate sense of language due to the common Phrygian grammar inherited genetically from their father, but Baphomet has also devoted a significant portion of his life to the study of languages. A wielder of words is a wielder of power. And the older the words, and the older the being plying them, the more power they have. Whatever is proceeding up the tunnel is chanting in a tongue he does not know.

“I believe,” he answers Ao Guang, “it... is time to leave.”

Light blazes from the crevice and the entire cavern emits a blinding flash like violet lightning.

* * *

When his eyes recover, purple spots dancing in his vision, Baphomet can make out the dark form of a creature squatting on top of the altar, silhouetted by the glowing wall behind it. Vertical pupils in eyes of burnished gold gleam in judgment over them. The beast lets out a whisper of a hisssss, and there’s the fragrance of lilacs, eucalyptus, frankincense resin and musk.

Ao Guang doesn’t so much kneel as buckle to his weakening knees. With a sputtering plop and squish, Dimmi loses control of his bowels and bladder. His whimpers sound for all the world like a sobbing parvulus child.

The landscape irises of Baphomet’s eyes grow wide as he recognizes the creature before them, one who hasn’t been seen or heard from since the bloody Second Holocaust, which ended almost twenty thousand years ago.

“Ama Kashshaptu...” he whispers in Sumerian. Mother Witch.

CHAPTER FOUR

Mendip Hills

The White Watcher watches.

It’s one of those nights with a flawless sky of the deepest black, the stars tiny pin-pricks of light, the full moon a pure white circle hole-punched in the ceiling of the world.

Circling high above what the watoto call Somerset County, in the South West of England, The White Watcher sees for miles in every direction, and his sight is good, perhaps the best in all this world for distance, in both the light of day and dark of night.

The land below is a map in relief, darkened shades of green, brown and blue, blotted with sparkling lakes, and woods of ash and maple, still garbed in their autumn leaves. Scribed with dead-straight canals, a few back roads and fewer freeways, rambling rivers and streams, intersecting dry-stone walls that divide pasture from field and dry land from bog. The White Watcher can make out the flat void of the Bristol Channel to the west. To the south he can’t quite see to the sea.

Directly beneath him the moors of the Somerset Levels shimmer through bristling black grass and a silken layer of mist. Just to the north, the dales of the Mendip Hills cup silvery fog, luminescent from the light of the moon. Beyond the hills the Avon Valley is a basin of cottony gray.

&nb

sp; Ireland, Scotland, Shetland, Wales, England, the Isle of Man, the Bailiwicks of Jersey and Guernsey, all are The White Watcher’s domain, his self-appointed ward. Every night he flies over these isles, making his rounds. He does not interfere, just watches. Alone. Unseen.

It was once the craggy peaks of Carrauntoohil, the tallest mountain in Ireland, that The White Watcher called home. Then the watoto began climbing it for sport in greater and greater numbers, so he relocated to Ben Nevis in Scotland, the highest peak in all the British Isles. More mountaineers came, and then the flying machines. He now spends the daylight hours in a cave along the northern coast of Ireland only accessible by diving past stony cliffs into the cold ocean waters, down to the hidden entrance well below the surface. The same cave he was dragged into when the Deluge drowned the world.

Something peculiar catches The White Watcher’s eye. Placing his arms against his body, he dives for a closer look, careful not to pass before the moon. He extends his wings to level out, keeping below the ridgeline and downwind, and alights on a wooded hilltop. Peering through the branches of an aged maple tree, he spies it, moving east along a path in the rolling forest half a mile away, keeping to the shadows. A dark shape of the kind he hasn’t seen in a very long time. Something not human. Something big.

* * *

Bödvar Bjarki trudges through the undergrowth, parallel to the dirt trail, picking his way over rocks and rotting tree trunks, ducking beneath branches, steering clear of the sharp light of the moon. An oversized canvas rucksack on a sturdy frame is slung on his back. From inside comes the muffled sound of sloshing water and a high gurgling voice humming a happy tune. He reaches over his hairy shoulder and raps on the top of the sack, which makes the sound of knocking on wood. “Shhhh!” he admonishes. The humming stops.

Paternus

Paternus Paternus: Rise of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 1)

Paternus: Rise of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 1) Paternus: Deluge, A Short Story

Paternus: Deluge, A Short Story Paternus_Rise of Gods

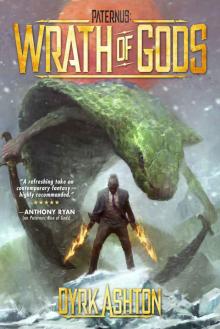

Paternus_Rise of Gods Paternus: Wrath of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 2)

Paternus: Wrath of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 2)