- Home

- Dyrk Ashton

Paternus: Deluge, A Short Story Page 3

Paternus: Deluge, A Short Story Read online

Page 3

Fintán’s first inclination was, once again, to save Cessair. This time he at least tried. In one bound he landed before her, but she placed her hand firmly on his chest and shook her head. The answer was clear.

Fintán’s mind raced as he considered their options. His eyes scanned the path leading from the beach to the village. They should have built on higher ground. But in his heart, he knew that only high in the mountains would they be safe, if even there. They must get to Myrddin’s Weal.

Fintán could travel there swiftly but the people could not, and he could never carry more than half a dozen in one trip. By the time he took one group and came back, it could be too late. And he knew Cessair would insist on being the last. The path they’d followed around the foot of the mountain and through the forest that first night was the safest way and the easiest, but it was far too long. They had to take a more direct route.

Fintán shouted for everyone to follow him without delay. They ran from the beach, not bothering to gather food or water. Fintán crested a rise and pointed in the direction they were to go, straight to the rising stone of the mountainside. There was a path there, they knew, shown to them by the habilis. Jack-knifing, treacherous, which had to be climbed more than hiked. As he ushered the last of them over the rise they heard another sound, beneath the wind and rain and retreating sea. A low roar. The hurricane was nearly upon them, a howling wall of night. He snatched up two of the younger Iberian children and, in his loudest voice, urged them all to run for their lives.

Cessair, Bith, Banba and the Iberian men helped the slowest in turn as they climbed. As, of course, did Fintán. The wind grew stronger and the rain assailed them like hard-flung stones. They slipped and slid as they scrabbled higher. Stones tumbled from beneath their feet, threatening to injure or dislodge those below. By the time they reached a thousand feet above the sea, the storm was so fierce they had to cling to the rocks to keep from being blown away—and the path ahead had crumbled, leaving naught but a sheer cliff face. There was nowhere left to go.

Then they heard a cry from above.

“Hail! This way!”

It was Myrddin Wyllt, and with him a dozen hearty habilis and several Druids, crouched atop an overhang above. As soon as Myrddin had become aware of the deadly seriousness of the approaching storm, he’d guessed Fintán would lead Cessair’s people this way, and headed down with these volunteers to help in any way they could.

Fintán scrambled to get everyone against the cliff, twenty feet below Myrddin’s ledge, which was high as they could go. Banba, helping Cessair with the children, caught her leg in a crevice and tripped. The bone snapped above the ankle. Cessair beckoned Fintán. He arrived and Bith lifted Banba to him. Cessair ordered Fintán to carry Banba to Myrddin immediately. The tone of her voice left no room for debate.

Fintán took Banba straight up the face of the cliff, past some of Cessair’s people who were already being hauled upward on knotted ropes. The sound of the storm was reaching deafening proportions when he delivered Cessair’s cousin into the arms of the Druids. He peered back down the cliff and saw Cessair at the back of the group with a child in her arms. Her eyes creased in an expression of loving gratitude. Then the wave hit and she was gone.

There’d been no surge, no rising water. None had time to shout in alarm. No warning at all. One moment the first to be hauled up were at the edge, Myrddin reaching for them, the next a black mountain of seawater, the top of it even with the ledge, had smacked them to oblivion, washing them into nothingness.

Fintán caught Myrddin as he fell back in horror. The faithful habilis tried to hang on to the rope. Six of them still clung to it as they were yanked into the raging abyss.

Nearly as quickly as it had come, the crest of the wave passed and the water level began to fall. The path below was bare. Fintán screamed, a high-pitched whistle-screech to stop the heart. He uttered in desperation, “Cessair!” and leapt.

By the time Myrddin could cry out his name, Fintán had plummeted into the flood, hitting with a high-flung plume. By bizarre coincidence, a school of salmon burst from the surface in fright, one of them big as a man. Three times it cleared the water, its body wagging high into the air.

By the time that story was told a thousand times, more than a few facts had been altered, added or omitted. To this day, many old tales of Éire insist that Fintán mac Bóchra could turn himself into a fish.

* * *

A Great Flood. Possibly the most common legend in all the world. Poeticized, spoken, sung, exhorted in scripture. There are flood stories from nearly every culture on every continent. Some are cautionary fables conveyed to the young, preached to the devout, proselytized to heathens. Others are simply narratives of survival. There are many different notions as to what caused the Deluge, and why. Most claim it was not a natural disaster but sent by a wrathful God, or gods, and in some cases a magical person or being. That humankind was punished, the earth cleansed because they’d become wicked, or in retribution for some terrible personal wrong, or simply an unkindness. Some are more outrageous and imaginative than others.

Nearly all the tales claim that people were warned of the pending disaster, and these warnings come from a variety of sources. Some say a god or gods informed their favorites. Others that God himself spoke, or sent a winged archangel. In some stories it was simply seen in the stars. A surprising number, however, say people were alerted by talking animals. In a tale from south Asia it was a gigantic fish. For one South American culture it was a sheep, another a llama. In west Africa a talking goat warned a young girl—and after the Flood, that same goat instructed her to have sex with her brother in order to repopulate the earth, though he knew very well there were other survivors nearby. He also wanted to watch. Those youths did not know the goat’s Truename. It was Baphomet.

As many claims as there are that folks were approached by speaking animals before the Flood, there are more that tell of people being saved by them during and after. And it is worth noting that by far the most Flood stories of animal messengers and saviors say it was a large bird, an eagle, a falcon, or a god who took that form.

* * *

The rain fell harder and winds cut deeper, but Myrddin Wyllt kept vigil from the cliff, desperate for a glimpse of Fintán, and, hoping against hope, Cessair and the fallen habilis as well. He’d sent the Druids back to the Weal with Banba, but the surviving habilis refused to leave him.

They were forced to retreat higher up the mountain as more waves came, mightier than the first, and earthquakes too. After each retreat, Myrddin waited, peering into the fuming waters below. He watched until long after dark, using a beam of light from his gambanteinn to pierce the torrent and swell.

But of Fintán mac Bóchra, or any of the others, there was no sign. Finally, he whispered an ancient prayer to the moon and stars and returned to the Weal.

* * *

Days passed and Myrddin fretted while the tempest raged and the earth rattled and jerked in fits. Then came the eye of the typhoon and a calm morning. The tsunamis had also ceased, at least for the time being. Knowing full well the probable futility of the endeavor, Myrddin set out in search of Fintán mac Bóchra.

He bid the habilis and Druids to scour the land, then made haste to a bluff on the nearest coast where he stripped off his robe and woolen cap. Wearing only a woven belt, and biting down on his gambanteinn, he dove, skinny and bare, into the furious froth below.

Myrddin combed the depths for days, every inch of this bay and the next, then back again. He found broken and bloated bodies of Cessair’s people and a few of his brave hapless habilis, but no sign of the living. In that time the eye of the storm passed and the onslaught of the cyclone resumed.

On the fifth day he was diving deep when, by sheer luck, or the compassionate guidance of mother Earth, the beam of his gambanteinn caught the flicker of glittering sticklebacks at the base of a tumble of rocks loosed from the cliffs by the quakes. The fishes seemed to beckon him, and Myrddin knew

better than to ignore a beckoning fish. He swam closer and saw something jutting from beneath a boulder. Fintán mac Bóchra’s leg.

The stone that trapped Fintán was bigger than a house, but it took only a few minutes wielding wand and word to break him free. To Myrddin’s relief, Fintán was still alive. But barely.

By that time the tsunamis had returned to pound the land into further submission, making the task of moving Fintán to the Weal impossible. But Myrddin knew of someplace closer where they’d be shielded from storm and surf.

Swimming backwards, well below the seething surface, he dragged his friend along the rocky coastline until he found the opening of an underwater cave deep beneath a high cliff. The gambanteinn clutched in his teeth lit their way through a winding tunnel, and up above the waterline. He used his belt to tether Fintán’s wrists over one shoulder, then climbed, up and up the vertical shaft deep inside the mountain.

The sounds of cyclone and ocean could not be heard, only Myrddin’s wheezing breath and the scrabbling of his fingers and toes on slick stone. At one point Fintán spasmed and gagged, clearing water from his lungs. Myrddin almost fell, but Fintán remained unconscious and became still once more. Then, finally, they were over a ledge to a dry cave, and Myrddin Wyllt collapsed. There he lay, clutching Fintán in his trembling arms, and wept, and fell fast asleep.

* * *

Though Fintán mac Bóchra did not die, and no one knows where that cave is save for he and Myrddin Wyllt, it has been referred to in fables ever after as Fintán’s Grave.

* * *

Fintán woke after a week but lay in despair with only the strength to weep for his lost love, Cessair. Myrddin came and went, brought food, reported on the weather, and offered what comfort he could, though it was not well taken. For forty days and forty nights the rain came down, fueled by cyclone after cyclone of unprecedented fury.

* * *

Fintán and Myrddin didn’t know then the extent to which the whole of the earth was being ravaged. In some places, rain fell at the rate of a foot an hour for weeks. Monsoons stalked inland plains, exhaling winds that reached two hundred miles per hour—and stayed that way for days on end. Rivers became lakes, lakes joined oceans, and deserts drowned.

Not all of nature’s wrath was discharged in the form of flood, however. Blizzards buried the far north and south. In other areas, icy fists of hail piled twenty feet deep. Tornados tore across lands where they’d never been seen before, and haven’t been since. Barrages of lightning came like airstrikes.

Nor was weather alone to be blamed for the devastation. Meteors bombarded the eastern Mediterranean, Arabia and northern Africa. Earthquakes rocked much of the world. Mountains crumbled. Valleys filled with mud. Volcanoes spewed rock, lava, and ash. Pyroclastic flows decimated city, village, forest and jungle alike. Fire literally fell from the sky. So did trees, frogs, fish, livestock, stones, and human bodies too.

In his silent cave, Fintán only knew grief.

* * *

On the morning of the forty-first day since the Deluge began, Fintán sat alone, nibbling ocean trout supplied by Myrddin Wyllt.

From below came a splash and a jubilant cry, “Fintán, my lad!”

Fintán crawled to the edge. Far down the shaft was Myrddin, half out of the water, clinging to the rock with one hand, waving his lit gambanteinn in the other.

“Come see, Brother! You must come see!”

Fintán stood with a groan, rolled his shoulders, stretched, and dove. The splash dislodged Myrddin Wyllt from the wall and left him spluttering.

* * *

Calm seas, a light breeze, and rainbows. More rainbows than should be possible, great streamers of victory arcing through the sky. And there was life. Petrels, Skuas, and Great Shearwaters screeched, soared and spun in exuberance. Tuxedo-clad puffins danced their clumsy dance on the rocks, bobbing orange-painted beaks at silver fishes that sprung from the sea. Humpback whales spouted and soared out of the water to splash playfully on their backs while porpoises performed triumphant aquatic ballets.

Myrddin’s heart swelled as he and Fintán watched from where they sat on a jutting rock. What would come to be known as the Deluge was done. It hadn’t meant the end of the world. At least not for all things. Fintán couldn’t deny the magnificence, the beauty, the celebration of life, but it brought him no delight.

In the days to come, Fintán searched the island. He and the habilis and Druids found bodies far inland, wedged under stones and tangled in trees. They gathered them gently and gave them a proper burial. None were Cessair.

Fintán widened his search, moving outward in an expanding spiral. In a matter of days he’d circumnavigated the globe, as only Fintán could, following much the same path he’d taken almost a year ago when he’d warned as many as he could of the coming disaster.

He visited all the continents in both hemispheres, north and south, and thousands of islands large and small. Everywhere he found bodies floating, bloating, bobbing, and bursting. Bird, fish, reptile, mammal, and man, all accompanied by the smell of sodden ripening death. Immense regions that once flourished were devoid of life. Fintán’s hope of finding Cessair faded, but he continued, for each time he thought to turn back he’d find more humans in need. The earth had not been completely scourged, as many had feared. Fintán discovered survivors trapped on mountaintops or high in trees, others floating on branches, hollowed logs and tattered rafts, even tree bark, gourds and in great wooden bowls. He aided all he came across, guiding or carrying them to safety.

He found other Firstborn as well, kin to him and Myrddin Wyllt. Soon after his arrival to what is today referred to as the New World, though it is as old as any, he came across The Great Turtle, swimming with dozens of bedraggled Lenape natives clinging to rocks and twisted roots embedded in his carapace. This was in the area of what are now called the Great Lakes—which was more like one great lake for a time after the Flood. Fintán pointed him in the direction of the nearest dry land, then continued on his quest.

In what is now the Pacific Northwest of the United States of America he greeted the much-loved Firstborn daughter, Mokosh. She’d saved the remnants of several tribes during the Flood, and was plucking more from the water onto reed rafts of her own making, then towing them to land. They called her Beaver (this was well before she migrated to the Slavic regions of Eurasia, where they worshipped her as Moist Mother Earth).

In the Great Plains he glimpsed the enigmatic and elusive Buffalo Woman, but when he approached she performed a forward roll and slipped away. Then he heard a shrill cry, calling his old Lakota nickname, “Wanblee Galeshka!”

He spied a young girl, caught in a cascade of rapids. He snatched her up and took her to a tall tree, gave her food, and pledged to send help—which he found soon enough in the form of one of the greatest benefactors of humankind in North America, the extraordinary Spider-Wife, known to some by her Truename, Kokyanwuhti, but to most as simply The Spider Woman. Nothing like her rapacious brother-mate, Maskim Xul—whom she’d escaped millennia before—and much larger than he, she’d once again saved thousands with her wisdom and web, just as she’d done for the Clovis people over ten thousand years earlier when a comet incinerated the continent in a blazing inferno that spawned many a moon of roaring wildfires and windstorms of flame, raising smoke and ash that cast out the sun. Fintán retrieved the Lakota girl, delivered her into the affectionate claws of the Spider-Wife, and sped on his way.

In the southwest of the same continent he found Kokopelli helping single survivors find viable partners with which to procreate, including a few of the Pima natives, whom Fintán had warned of the pending disaster almost a year before. Fintán continued south, following the winding ranges of Central America. There he glimpsed a blue-shining flash in the distance, a blackbird, and his breath caught in his throat because he thought it might be Munin, The Raven, whom he hadn’t seen in a myria and sorely wished to speak with, but then it disappeared—proving it probably had been Munin, aft

er all.

Fintán plucked Chorote boys from rushing waters in eastern Paraguay, paid his respects to the kindly Llama with his Quechuan wards on Mount Villca Coto, and the gentle Sheep with his human friends high in the Cuzco range of Peru. Both were saddened at hearing of the loss of Cessair. They knew of her only by reputation, but they’d also lost loved ones many times over, as all Firstborn do, and they knew the pain was as intense with each, the emotional wound every bit as raw and deep.

Fintán sped west over the wide ocean, helping all in need. Then, high over the South Pacific, he crossed paths with a great white dove that clutched a leafing twig in one foot and a note in the other. The message was written in Noah’s scrawl. He and his family had survived, and it named the place where they’d finally touched ground.

Noah’s Ark hadn’t landed on Mount Ararat in Turkey, as is commonly claimed, or the biblical Mt. Sinai. Nor was it perched atop Mount Judi, or high in the Malaya Mountains (the southern range of what are now called the Ghats of western India) as alleged in the Hindi Matsya Purana—those were the arks of others of Noah’s clan, or those he’d sent out to other centers of civilization before the Deluge—but plunk in the mud of the Djilinbadu plains of western Australia.

* * *

Noah greeted Fintán with delight and embraced him tight. He explained they’d intended to sail to Fiodh-Inis as planned, but final loading and boarding of the ships took longer than expected in the rain and winds that preceded the Flood, and they couldn’t catch the bloody unicorns. They’d finally embarked only days before the Deluge hit. The ships had become separated, and forty-three days later, Noah’s Ark had been stranded here.

Fintán told Noah of his own travails. Noah showed no sorrow for his son, Bith, for he’d denied Bith’s existence long ago, but at hearing of the loss of his granddaughter Cessair, his heart fell. Fintán only added to his anguish when he explained that Noah’s homeland in Sumeria had been devastated. Being stubborn and proud, Noah insisted on returning anyway.

Paternus

Paternus Paternus: Rise of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 1)

Paternus: Rise of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 1) Paternus: Deluge, A Short Story

Paternus: Deluge, A Short Story Paternus_Rise of Gods

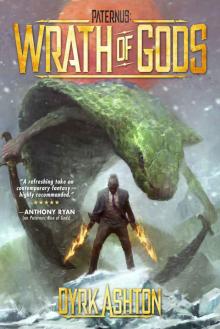

Paternus_Rise of Gods Paternus: Wrath of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 2)

Paternus: Wrath of Gods (The Paternus Trilogy Book 2)